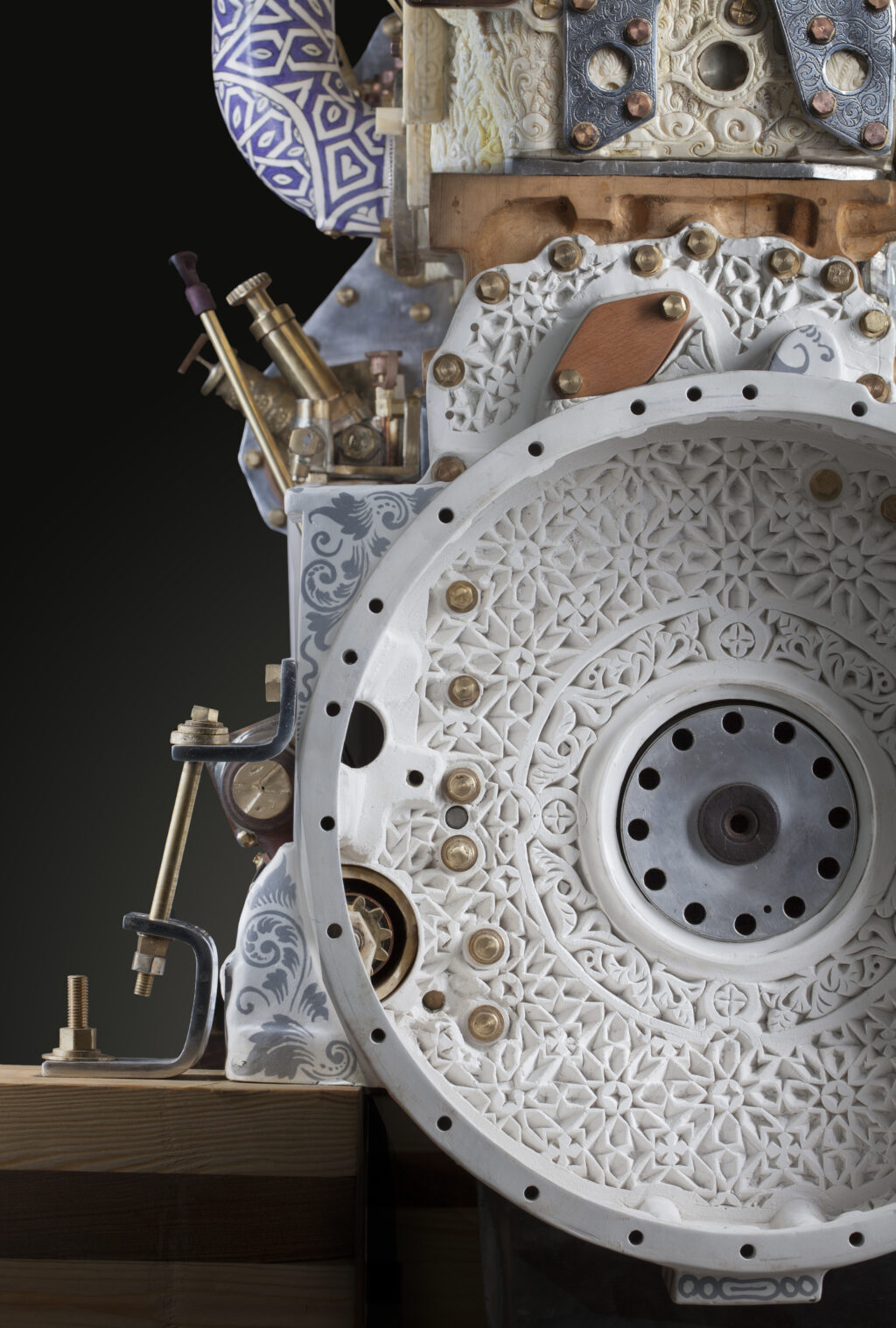

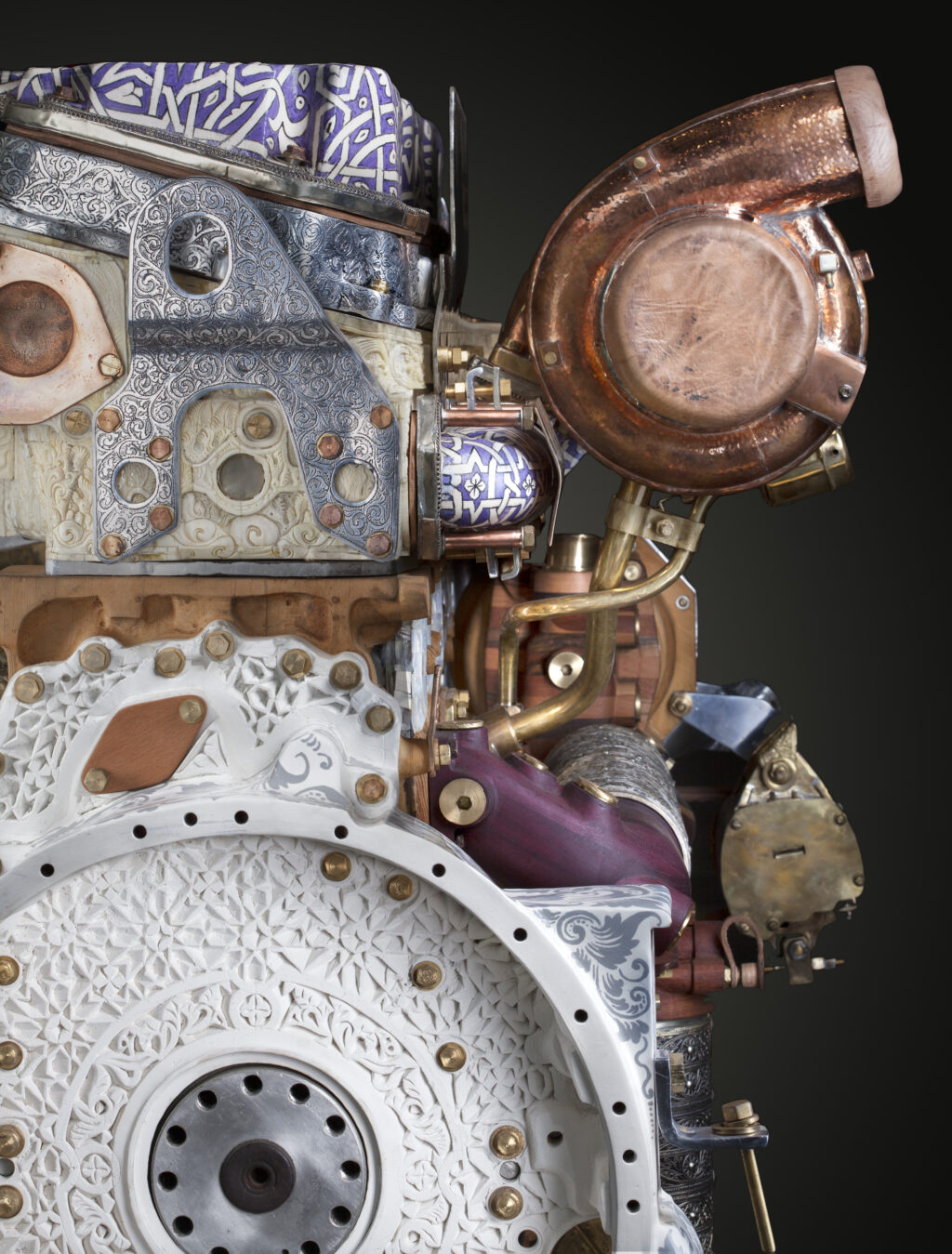

Mixed media (44 materials): Middle Atlas white cedar wood, high Atlas red cedar wood, walnut wood, lemon wood, Purple Heart wood from Brazil, Wenge wood from Congo, Tatajuba wood from Suriname, orange wood, ebony wood of Macassar, mahogany wood, Thuya wood, Moroccan beech wood, pink apricot wood, mother-of-pearl from Java, yellow copper, red copper, forged iron, recycled aluminium, nickelled silver, silver, tin, cow bone, goat bone, camel bone, malachite of Midelt, agate, green onyx, tigers eye, Taroudant stone, sand stone, Fibrous gypsum selenite (stone), red marble of Agadir, black marble of Ouarzazate, white marble of Béni Mellal, pink granite of Tafraoute, goatskin, cow skin, lambskin, resin, Ourika clay, terra cotta with vitreous enamel, paint, cotton, Orange flower oil.

Size: 160cm x 160cm x 132cm

Weight: 500 kg (800 kg once crated) – Composite sculpture (about 300 parts)

Edition: Unique

Courtesy: Collection Fries Museum, Leeuwarden/The Netherlands

Photo: Jens Martin (for Marrakech Biennale 6 NOT NEW NOW)

Craftsmen involved: Abdelkhader « dragon » Hmidouch, Abdeljalil Ait Boujmiâa, Mohamed Ouhaddou, Soufian Sahli, Mehdi Ghinati, Mohamed Zouita, Said Charki, Wayan Lila, Budi Hartono, Pak Sunan, Pak Rahim, Abdelghafour Boutkrout, Lahsen Iwi, Adbelatif Boulaâdam, Mohamed Elghamssi, Chikhaoui Khamssi, Mustafa Sahli, Abdelali Sadok, Mustafa Jaouale, Abdelali Arib, Mustafa Moufdi, Abdelali Ezhidi, Ridouan Errahel, Abdelrrazak El Ghadoui, Ittaki El Moussine, Tarek Maknaoui, Fuzia Yaagoub, Morad Ouizlem, Abdelrahim Ait Boujmiâa, Société Afritour, Abdelrahim Boutkrout, Lhsan Ait Hadouch, Abdelatif Farhat, Hassan El Mouadine, Id-nacer El Houssine, Mohamed Ait Boujmiâa, Omar Saadouni, Youssef Ait Ali, Hassan Himed, Ahmed Id-Nacer, Mbarek El Maniai, Mustapha Ouizlem

D9T (Rachel’s tribute), a reconstructed C-18 ACERT, consists of 290 parts made from 46 different materials from all around the globe. These components were produced by 41 different artisans. This endeavor was intended as a collaboration between craftsmen from two countries that both have approximately twenty per cent of their respective active workforce in craft: Indonesia and Morocco. Van Hove had long hoped to bring Asian and African craftsmen together so as to stimulate an exchange of knowledge and experience. The D9T (18L Turbocharged-After cooled In-Line 6, 4-Stroke-Cycle) engine is derived from the engine of a D9 series Caterpillar, a bulldozer that has profoundly affected both continents. The D9 was originally designed in 1954 to help with the construction of new infrastructure in developing countries, but was later also used for military purposes (most famously the IDF makes great use of the D9T in the West-Bank…). The piece is dedicated to Rachel Corrie, an American activist who was crushed by an D9T powered by that same engine in Gaza in 2003.

« Here is the heart of the beast made-up in mother-of-pearl, corrupted by tenderness. What happened to it? It was eaten alive. Delivered up to the Marrakesh studio, the motor was dissected down to its most fragile bones, studied in its most intricate angles, duplicated to the nearest millimetre. And the muscle-man was divided up entirely, reconstructed with its new textures. Devouring, ingesting, reconstructing: cannibalistic poetic justice, Friday sits down to dinner again. In its juices, its denied knowledge, the firepower of automated technicism, the death of Rachel, sacrificed on the altar of the latest colonial barbarities. Cultural cannibalism, the metamorphosed engine is the distant echo of the following dark prophecy written in 1928 in Brazil by Oswald de Andrade in his Cannibalist Manifesto: “Cannibalism. Absorption of the sacred enemy. To transform him into a totem. (…) It is the thermometrical scale of the cannibal instinct. Carnal at first, it becomes elective, and creates friendship. When it is affective, it creates love. When it is speculative, it creates science.”.

Devouring, knowing, loving: it is not about hating the C18, taking an axe to it, but rather dismantling it—lovingly, methodically—in order to reconstruct it. “It is common knowledge,” wrote Lévi-Strauss, “that the artist is both something of a scientist and of a ‘bricoleur’. By his craftsmanship he constructs a material object which is also an object of knowledge”.

And what is there to know? The object to dismantle, first of all. A stranger which requires that one become a stranger. To become an “exoticist”, Segalen says, to embrace exoticism, in the sense of “the perception of Diversity”, of “the knowledge that something is other than one’s self”. And this exercise, imposed in this case on the artisans applying their art to a mechanism foreign to their art, “is not that kaleidoscopic vision of the tourist or of the mediocre spectator, but the forceful and curious reaction to a shock felt by someone of strong individuality in response to some object whose distance from oneself he alone can perceive and savor.” “Exoticism,” Segalen points out, “is therefore not an adaptation to something; it is not the perfect comprehension of something outside one’s self that one has managed to embrace fully, but the keen and immediate perception of an eternal incomprehensibility”.

In short, knowing it is strange, but still knowing how its workings work, screw by screw, belt by cylinder head. Also, knowing one’s ability to remake said workings, to experience oneself in its recomposition. »

From the essay Friday’s Feast (Les Noces de Vendredi) by Laurent Courtens, which was originally published in the official program accompanying the exhibition of D9T (Rachel’s Tribute) at the 6th Marrakesh Biennial in 2016